Cantu a Tenore, an Echo from The Ancients

Echo from The Ancients

Imagine yourself in Sardinia. Midway along the Mediterranean Sea, amazing summer sun, and just cool little places all around. One night after dinner you go for a stroll to explore the city of Orosei on the eastern coast, and you start hearing some weird metallic drone-like singing, in the distance.

You’ve never heard anything like it. The closest you can compare it to is a Death Metal singer that had found the joys of Buddhist meditation.

Once you find its source you realize it’s a group of men singing in a circle in a manner you’ll never forget.

Congratulations! You’ve encountered singers of Cantu a Tenore.

It’s a part of Sardinia’s pastoral and musical heritage, and a form of polyphonic singing traditionally performed with 4 voices in Sardinian, the local language. They are named: su bassu, sa contra, su mesu oghe, and sa oghe.

MUSIC

The Tenores Di Bitti is one of the most famous groups and has helped in making the tradition known all over the world

Among its most recognizable features are the grittinness and metallic sound of the bassu and contra’s voice, which along with the mesu oghe form an accompanying chorus. These 3 voices constitute the su tenore and sing a series of rhythmic nonsensical syllables (‘bim, bam, bom’ are some that are used) while the lone oghe cites a given piece of poetry or prose that helps mark the rhythm and character of the song. It’s traditionally sung a cappella, i.e. without accompanying instrumentation, and in a close circle formation to allow the performers to hear each other properly.

To all of you musical nerds out there, the theory goes more or less like this: Visualizing it through the keys of a piano, the bassu produces the lowest tone, a fifth below the contra, and the mesu oghe harmonizes with the previous two by singing major thirds, fourths, and at times even fifths and sixths above. More or less in the middle of the range rests the oghe.

What you see above is a basic layout of the harmonization transposed onto the keys of a piano

The bassu and contra are the harmonic pillars on which the other 2 voices sit.

Going a little bit deeper into the technique itself on these 2 lower voices; In effect, they constitute a type of polyphonic throat singing. It makes use of an anatomical feature common to all of us but only used as a singing instrument by a select few since it requires quite a lot of training and habituation.

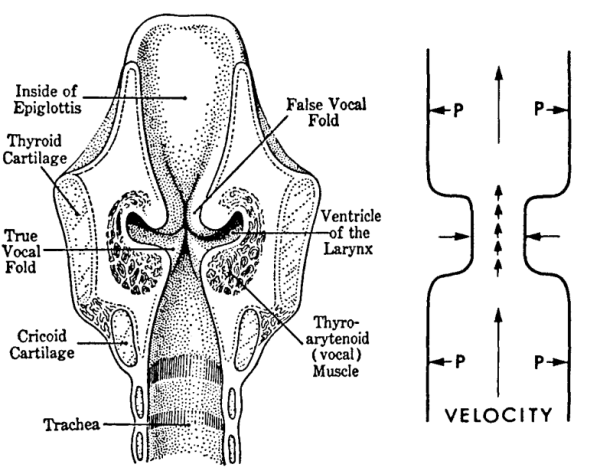

FALSE VOCAL CORDS

This feature is the vestibular folds or ‘false vocal cords’. They are located in our larynx, commonly named voice box, and are in fact not strings. They are closer to a mucous-covered membrane that sits above our vocal cords and trachea, to prevent liquids and solids from descending into them.

Generally speaking, when we want to produce sound with our vocal cords, several things occur. Firstly, the airflow being pushed out of the lungs increases in volume and speed. These increases push both sets of vocal folds apart, which causes a tendency for them to return to their original positions. The reason for this is twofold: Firstly their elastic nature implies a return of force against the physical stimulus, in “search” of equilibrium; And in consequence, the Bernoulli effect states that any increase in speed of flow on a fluid dictates a decrease in static pressure at the site of the constriction. Long story short, a conscious effort (muscle activation) in closing a vocal cord, adding on to its elastic nature and airflow pressure causes an ever-increasing tendency for it to close. Once it does, airflow coming in opens them up again, and the cycle repeats, producing a voice.

A graphical representation of a human larynx and surrounding structures as well as a schematic view of the Bernoulli effect

This is true for the vocal cords, but not really for the vestibular folds. These in comparison have much less muscle tissue and quite a different shape that makes it unlikely for them to produce sound as reliably. Their usage in singing is therefore a much more conscious effort, and perhaps some anatomical fortune, and involve a lot of training and awareness of one’s own body.

Curiously enough it is possible to “sing” using only the vestibular folds, but you’ll end up with a very rough-sounding growl. This is used quite a lot in some subgenres of Heavy Metal, such as Death Metal.

Returning to the subject, in Cantu the bassu does in fact make use of the false vocal cords when singing. Their vibration will produce a sub-octave in relation to the sound the real ones create. Put simply, the same tone but lower down. This is called ‘Period Doubling’¹ or ‘Vestibular Diplophony’² since it makes use of the “true” and false vocal cords at the same time. The contra however only makes use of these by keeping them tensed up, which does not allow for the generation of a lower tone. Fortunately, it still adds to the allure of the performance by creating a very metallic sound.

It’s also noteworthy that once a singer’s role as one of these 2 voices is defined, it’s ill-advised by fellow singers and masters to attempt to change vocal type without proper experience. This is due to the long period of habituation needed for the false vocal cords to be able to produce sound safely. The constant fluctuation between roles might input too much strain on them and cause long-term damage.

Below I bring you 2 different styles of Cantu; A slower method (Tenore de Orosei) in which chord changes throughout the song are more emphasized; And a more rhythm imperative option (Tenores Di Bitti) which, if you’re that kind of weird, will make for a great meditative tool:

Tenore de Orosei – A una rosa (Voche ‘e notte antica); 1998

Tenores Di Bitti – Su Cojoviu novu; 2003

ETNOGEOGRAPHY

Throat singing appears in several cultures around the world, but mostly in colder climates. There are, however, some common aspects among these different traditions: They belong to cultures that lived or live isolated, as a consequence of the territory’s physical features and its history; and most of them relied or still rely heavily on shepherding as a tool for sustenance and survival.

These are the general locations that are home to some of the cultures that still use guttural singing techniques: The Inuits of North America; The Xhosa people in South Africa; The Tuvans and Buddhist sects in Central Asia; And the Sardinians in the Mediterranean;

The most famous among them is perhaps the Tuvan method, which belongs to a shared cultural continuum of polyphonic singing traditions in Central Asia. This specific example includes 2 techniques also utilized by the Sardinian bassu and contra, only, in this case, they take the names of Kargyraa and Khoomei, respectively. There are some more noteworthy examples like the katajjaq belonging to the Inuits of North America, the meditative vocals produced by Buddhist monks of the Gelukpa sect in Tibet, or the eefing technique of the Xhosa people, in South Africa.

One of the least known examples is the Cantu a Tenore from Sardinia.

One of the least known examples is the Cantu a Tenore from Sardinia.

It is more frequently heard in the center of the island, most notably in the regions of Barbagia and Baronia where some of the strongest living traditions of cantu exist and are very deeply embedded in the daily life of local communities. It’s traditionally sung in sheepshearings, in bars called su tzilleris, and also in more formal events such as weddings and religious festivities. It survives mainly through oral or recorded transmission and imitation and doesn’t have rigid schemes or reliance on written scores.

Its relaxed and spontaneous nature, along with the fact that it is “at home” in colloquial everyday situations, is much of the reason why it has survived rather unscathed from the powerful influence of globalization to today. In fact, in central Sardinia, its practice is embraced by many younger citizens and even considered by some as ‘alla moda’, or fashionable.

Each region has its specificities regarding lyrics, that amass subjects both sacred and profane. This is a consequence of the island’s physical and cultural isolationism, as well as of its topographical features.

The texts include ancient and more contemporary poetry pertaining to more “relatable” topics such as emigration or politics. Other than these it’s also possible to listen to old tales, satire, and love songs.

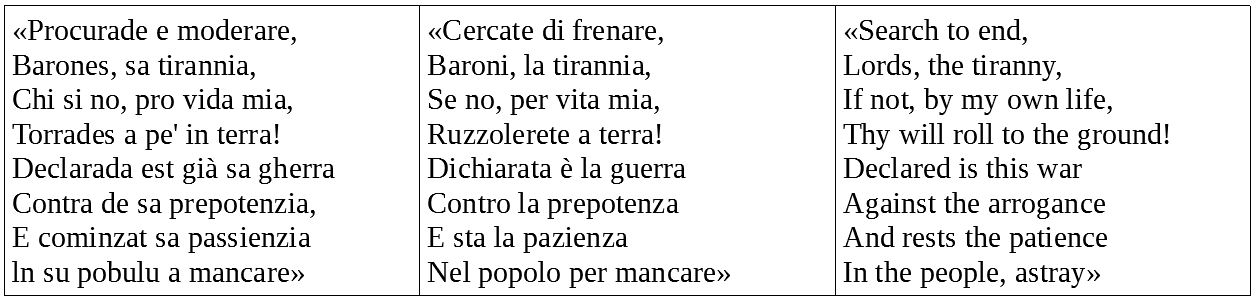

An example of a political text is this XVIII century verse from an anti-war piece of poetry, in Sardinian, and translated to Italian and English:

“Sa patriotu sardu a sos feudatarios” is a revolutionary anti-feudal song, written to protest the dreadful state of the island’s affairs, that worsened thanks to the incompetence of the feudal lords; Written by Francesco Ignazio Mannu in 1794

ETYMOLOGY, ORIGINS, AND HISTORY

What about the name, Cantu a Tenore? One could easily assume it should have some relation to the Italian tenors made famous in the whole world along the past century.

In fact no, nothing of the sort. It has to do with the word tennere, an Italian verb that means to hold or keep. It is thought that in the Medieval period, the word acquired the contextual connotation of grabbing or seize (acchiappare) and weaving (tessere). These perfectly illustrate what happens when the 3 follow-up voices come into play. A capture of the basic melody sung by the soloist is then harmonized by the 3 other voices.

Today it is part of UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage, but unfortunately, its origins are not yet “set in stone”. Even though written  sources attest to the appearance of this tradition around the 15th century, some who study the subject claim it dates back to the island’s Nuragic period. This claim, if corroborated would push its genesis back hundreds of years, to as far back as the 18th century BCE, or even earlier.

sources attest to the appearance of this tradition around the 15th century, some who study the subject claim it dates back to the island’s Nuragic period. This claim, if corroborated would push its genesis back hundreds of years, to as far back as the 18th century BCE, or even earlier.

According to the proposals of some researchers, its rhythmic syllables may have been a way for the ancient peoples living in Sardinia to transmit ideas, concepts, dreams, or other types of information without having to make use of writing (Deplano, 2011), before it even became ubiquitous in the sub-continent.

Others in fact connect it with the Semitic languages of the Near East, through a phonetic particularity named pharyngealization. Compared to guttural vocalizations this is a relatively more complex phenomenon since it involves the production of vowels and consonants not only in the larynx but also on the soft tissues of the posterior portion of the oral cavity and the pharynx. Interestingly enough, this being the case would indicate a plausible closer cultural and perhaps even physical connection between the homologous Mediterranean and Proto-Semitic peoples in the basin during the first 2 millennia BCE.

Whichever case it may be, it’s a fact that for thousands of years the island of Sardinia has been at the crossroads of many empires, civilizations, and cultures that changed history.

As a general understanding among the inhabitants and their respective ancestors, the sounds produced by the singers resembled a sort of “nature’s soundtrack”. As such, the bassu emulates a cow’s bellow, the contra the bleat of a sheep or goat, and the mesu oghe the passing of the wind. The lone oghe represents the shepherd.

Even though there is no written or symbolic evidence of these associations, they serve to illustrate the tradition’s deep connection with nature.

It’s certainly an acquired taste to listen to, but also an undeniably interesting product of a rich culture that resists and beguiles visitors with a very ancient charm.

SOURCES

Articles, Books, and Reports:

Antonaci, A. et al (2013). Digital technology and transmission of Intangible Cultural Heritage: The case of Cantu a Tenore. 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage). https://doi.org/10.1109/DIGITALHERITAGE.2013.6744741

¹ Bernardoni H. et al. (2006). Period-doubling occurrences in singing: the “bassu” case in traditional Sardinian “A Tenore” singing. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.61.9539&rep=rep1&type=pdf

¹ Bravi, P. (2012). L’accompagnamento vocale nel canto a tenore. Core Ac Uk. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/11693871.pdf

Websites:

² Bortoluzzi, G. (2020, July 31). Le voci del Canto a Tenore. Armonici.it. https://blog.armonici.it/le-voci-del-canto-a-tenore/

Canzoni contro la guerra. (2007). Canzoni contro la guerra: Francesco Ignazio Mannu – Su patriottu Sardu a sos feudatarios [Procurad’ e moderare]. Anti War Songs. https://www.antiwarsongs.org/canzone.php?id=5768〈=it

C, K. (2020, October 16). The Mysterious Nuragic Civilization of Sardinia. Ancient Origins. https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-ancient-traditions/nuragic-sardinia-004841

Dedola, S. (2021, February 16). Su cantu a tenòre. Linguasarda. https://linguasarda.com/su-cantu-a-tenore/

Deplano, A. (2011). Andrea Deplano. Andria Deplano. http://www.andriadeplano.it/bidustos.htm

Huckvale, M. (2017). PALS1004 Introduction to Speech Science. Phon. https://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/courses/spsci/iss/week4.php

La Barbagia. (2018, January 16). “‘Il canto a tenore di Orgosolo’” dal 1955 al 1961. https://www.labarbagia.net/notizie/letteratura/12131/sos-tenores-de-orgosolo-da-su-1955-a-su-1961

Mion, A. (2019, April 24). Il canto a Tenores di Tenute Dettori. Intravino. https://www.intravino.com/primo-piano/il-canto-a-tenores-di-tenute-dettori/

Nosowitz, D. (2019, October 13). The Many Pleasures of Sardinian Throat Singing. Atlas Obscura. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/sardinian-throat-singing

Oberton. (2018, May 2). Sardinia –. https://www.oberton.org/en/overtone-singing/styles/sardinia/

Pegg, C. (n.d.). Throat-singing | music. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/art/throat-singing

Quark Expeditions. (2016). Inuit Throat Singing – A Mesmerizing Experience. Explore Quark Expeditions. https://explore.quarkexpeditions.com/blog/inuit-throat-singing-a-mesmerizing-experience

Regione Autonoma della Sardegna. (2018). Sardegna Cultura – Argomenti – Musica – Canto. Sardegna Cultura. https://www.sardegnacultura.it/j/v/258?s=20336&v=2&c=2700&t=7

Sedda, A. G. (2020, January 8). Suoni dalla Sardegna. L’animo antico dei Canti a Tenores. Portale Sardegna. https://www.portalesardegna.com/blog/nullacomelasardegna/suoni-dalla-sardegna-lanimo-antico-dei-canti-a-tenores/

Scuola di Canto Difonico e Throat Singing. (2019). Cos’è il canto difonico? Scuolacantoarmonico. https://www.cantodifonico.eu/l/cose-il-canto-difonico/

Smithsonian Institution. (2021). Throat Singing: A unique vocalization from three cultures. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. https://folkways.si.edu/throat-singing-unique-vocalization-three-cultures/world/music/article/smithsonian

Tenores di Bitti. (n.d.). Cenni storici e descrizione dei canti del repertorio bittese. http://www.tenoresdibitti.com/cenni.htm

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Dge-lugs-pa | Buddhist sect. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Dge-lugs-pa

UNESCO. (n.d.). Canto a tenore sardo – Unesco. UNESCO Beni Culturali. https://www.unesco.beniculturali.it/projects/canto-a-tenore-sardinian-pastoral-songs/

UNESCO. (2011, January 11). The Canto a tenore, Sardinian Pastoral Songs. UNESCO Multimedia Archives. http://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/document-1748

Wolff, H. E. (n.d.). Afro-Asiatic languages – Proving genetic relationship: problems of internal comparison. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Afro-Asiatic-languages/Proving-genetic-relationship-problems-of-internal-comparison#ref1023734