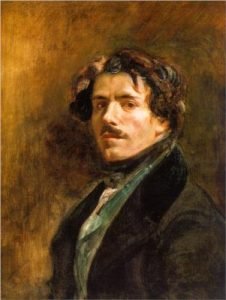

Delacroix and the Leadership of the People’s Freedom

Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix (Öjen Dölakrua) (26 April 1798 – 13 August 1863) is one of France’s most important Romantic painters. His father is the statesman Charles Delacroix. However, it is also claimed that his real father is the diplomat Talleyrand, who is a family friend of C. Delacroix. E. Delacroix resembles Talleyrand in terms of physical appearance and character. Throughout his painting career, Talleyrand protected and supported him.

Visual (1)

Delacroix’s childhood years were spent in Charenton and later in Paris. His father passed away when he was only 7 years old in 1805. They settled in Paris in 1806. His talent for painting quickly caught attention while he continued his education at the Royal College. However, his desire to become a painter emerged while working in his uncle H.F. Riesener’s studio.

In 1815, his uncle recommended him to Pierre Guérin, a renowned painter and a student of the famous painter David, who had gained fame as a neoclassical artist. The young 17-year-old entered Guérin’s studio. Meanwhile, he visited the Louvre Museum and copied examples of the works of the great masters.

Although the influence of the Renaissance painter Raphael can be seen in his early works, Delacroix gradually embraced a more free style and was influenced by the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens for a while.

The most significant event in Delacroix’s life is undoubtedly his six-month trip to Morocco, Algeria, and Spain. He embarked on this journey thanks to the Government Member and President of the Council Thiers, who recognized his talent. Thiers arranged for him to join the diplomatic delegation heading to Tangier. Thus, the six-month tour began.

The ethnic diversity, variety of colors, richness of light, and local costumes he saw in these regions fascinated him. Regarding this, Delacroix said, “I will always keep the dream of this country in my mind. The men and women of this strong race will remain vivid in my memory until the end of my life. I found true beauty in them” [1].

He first went to Morocco and stayed there for months, encountering elements that would allow him to make numerous sketches. This trip resulted in a revolution in his understanding of art. It marked the beginning of a process in which he gradually moved away from his classical period and embraced romantic tendencies. After the trip to Morocco and Algeria, his romantic tendencies became more apparent. However, it took time for him to find his true identity as an artist. Afterwards, he became an immortal painter.

He had a personality that enjoyed drawing inspiration from books and significant events. Although he was an artist who embodied the emotional elements of Romanticism in his art, he never admitted to being a romantic artist throughout his life.

He passed away on August 13, 1863, in his studio on Furstemberg Square in Paris. During this period, Delacroix’s health was not in good condition, and he was unable to train students. However, he influenced a young generation who were inspired by him.

He greatly influenced Impressionist artists. Renoir and Manet copied his paintings. Modern artist Pablo Picasso also interpreted Delacroix’s works and worked on his piece titled “Women of Algiers.”

Delacroix and His Exemplary Works:

In 1822, Delacroix sent his paintings “Dante and Virgil” and “The Massacre at Chios” to the Paris Exhibition. These works instantly created a stir in the art circles. Despite receiving fervent praise from some critics, the two paintings, which were purchased by the state, also generated negative reactions.

Visual (2)

Visual (3)

“The Massacre on Chios” has gained great fame with its painting. This painting depicts an event that took place on the island of Chios. In the eyes of the French people during these centuries, the Turks were committing genocide against the Greeks. This created sympathy for the Greeks. In the artwork, it portrays sick and dying Greek civilians who have suffered a massacre by the Turks on the island of Chios. As a leading painter of the new romantic era, Delacroix quickly realized that the French would show great interest in this theme, and it happened as expected. The artwork was purchased by the state. However, there was a problem in that the painting gave a different impression than what was intended, according to critics. Critics have suggested that the most striking and genuine element in this artwork, the Turkish figure on horseback, may also express admiration for the Turkish soldiers due to their prominent presence. Nevertheless, regardless of the reason, this artwork is a step towards the painting “Liberty Leading the People.”

“The Women of Algiers in their Apartment, 1834”

Visual (4)

Death Of Sardanapalus, 1827

Visual (5)

Delacroix and the Romantic Movement

The Romantic Movement is an influential movement that emerged primarily in England, France, and Germany in the 18th century. It not only influenced painting but also literature and philosophy. Many followers of this movement were followers of the neo-classical movement.

Neo-classicism, on the other hand, is a new version of the old. It maintains the current form of a previously existing idea and movement. Artists in this movement aimed to create new classics. In fact, this movement, which originated in Germany, had the greatest impact in France.

Romanticism is a result of the changing world and the industrial revolution. The human race, eager to break free from molds and express themselves, wanted to fully engage with life and sought to do the same in art. The artist placed themselves more prominently and aimed to break free from classical ideas and molds inherited from the past. The artist’s perspective, thoughts, emotions, and imagination are now more important and integrated into the artwork.

Romantic artists strive to break free from rules, measurements, and limiting lines. They have taken the artist themselves, their emotions, and the artist’s world as a source of inspiration for these elements [2].

When we delve into the past of Romanticism, we can speak of many factors that contributed to its emergence. These include:

- Renaissance and Reformation

- New Territories

- Scientific Studies and Inventions

- Transition from Trade to Industry

- Enlightenment in Thought

- French Revolution: The fundamental factor in Delacroix’s work is the French Revolution.

This influence is not limited to the field of painting but also extends to many other areas. For example, all other areas of art, religion, and philosophy are just a few examples. This process, in harmony with the evolving state policies in individuals’ lives, has also influenced art. Human sensitivity is now at the center. Interest in landscape paintings increases. In addition, there is an interest in the East, the depiction of the East in paintings, mystical compositions, the portrayal of emotional states beyond tangible objects, and the actualization of these emotional states as the main subject of the painting… In this way, the art of painting has found its soul and has had the opportunity to delve deeper. The unseen has become as important as the visible.

The subjects in this movement can be from history as well as contemporary issues. The artist conveys a past or contemporary event, adding their emotions to it, resulting in an art that is free from rules and molds. Now, the artists’ imaginations are also present within the artworks.

FREEDOM THAT LEADS THE PEOPLE

Visual (6)

Story of the Artwork:

Delacroix’s painting titled “Freedom Guiding the People” tells the story of the struggle for freedom and its relationship with class differences. This artwork, which holds historical significance, is also the most famous painting depicting urban uprisings.

The painting was purchased by the French government in 1831 but was considered completely contrary to traditions. However, it began to be exhibited regularly after 1863.

The work of the French Romantic artist Eugéne Delacroix (1798-1863) combines two main elements: allegory and reality. The allegory here represents ‘freedom’ itself. The reality part, on the other hand, depicts an actual event, making it one of the earliest examples. Additionally, each figure represents a segment of society, shedding light on the era in which it was created. It is also connected to the literature of the period. Its multidimensionality has made it one of the artist’s most remarkable works, both at the time of its creation and in later years. The painting portrays a real event.

When it was exhibited in the Salon in 1831, the catalog listed it as “July 28: Freedom Guiding the People.” This specific date refers to the day of the most intense clashes around the Hotel de Ville in Paris during the July Revolution of 1830.

The uprising that took place on July 27-28-29 is referred to as the Second French Revolution or Trois Glorieuses (Three Glorious Days). The king’s behavior, particularly that of King Charles X (1757-1836), was among the leading causes of the uprising. In his pursuit of absolute monarchy, the king did not hesitate to make a series of harsh decisions. Appointing Prince Jules de Polignac (1780-1847), a nobleman, as the head of the government was interpreted as a counter-revolutionary move even by other absolutist kingdoms in Europe. New elections were held in July, and despite the government’s party receiving only a third of the votes, Prime Minister Polignac refused to relinquish power, claiming that “God had bestowed upon him the duty to save France.” He annulled the elections and decided on new ones. On July 25, he also abolished press freedom. These three decrees served as a signal for an uprising. The opposition called upon the workers to take action. The publication of these decrees, which amounted to a genuine coup, led to an extraordinary unity among the people of Paris. On July 28, hundreds of barricades were set up in the streets of Paris. The soldiers joined the uprising. On July 29, the revolutionaries seized the Louvre and Tuileries Palaces. The leader of the opposition, La Fayette (1757-1834), was appointed commander of the National Guard. A provisional government was established in the City Hall, under the presidency of Casimir Perier (1777-1832). The tricolor flag was hoisted. The insurgents wanted to declare a republic. However, journalist Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877) nominated the Duke of Orleans as the candidate for the throne. La Fayette declared the Duke of Orleans as the commander-in-chief of the kingdom. After King Charles X went into exile in England, Louis-Philippe d’Orleans (1773-1850) was proclaimed the King of France by the assembly. While this uprising depicted by Delacroix was one of the current events of his time, nearly every source referring to this painting states that it is an allegory. The reason for this is the female figure advancing on the barricade with the French flag in her hand. This female figure represents liberated France, while those around her represent various segments of the revolutionary people.

a-The Figure of Freedom:

In the painting, the figure of a woman is used as a symbol of freedom. This is quite surprising because in Western art, freedom is not typically associated with women. While women are often depicted representing qualities such as modesty and serenity, here we encounter a completely different portrayal of a woman. This woman is not the composed and passive figure we commonly see in Western art, but rather a woman in motion, with disheveled hair, advancing on barricades with her chest exposed.

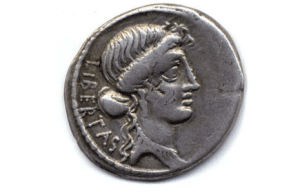

1-Libertas:

When we look into the history of this figure, the first example that comes to mind is ‘Libertas,’ a Roman goddess.

Visual (7): Figure of Libertas, Brutus Coin

Visual (8): Figure of Freedom, Seal of the French Republic Government, 1792

On the coins, we see a crown on the figure’s head. However, in Delacroix’s depiction of the symbol of freedom, the female figure is not wearing a crown but a Phrygian cap. This cap represents freedom. It is known as a headgear that symbolizes the new status of emancipated slaves in the Roman Empire.

Visual (9): Detail

The female figure in the artwork is quite dynamic. This figure in motion is a testament to the dynamism and liveliness of the revolution and protests. The once-static figures have now become more animated, and one reason for this is the vibrancy and dynamism of the era.

As mentioned earlier, the woman figure depicted by Delacroix is a disheveled figure. It is different from the familiar depiction of women we have known and seen. Additionally, this figure has multiple sources of inspiration.

2-France:

The figure, both with the flag in her hand and through the allegory depicted, represents France in tangible form. It portrays a liberated France, a France in motion. This transformation was not easy.

3-Woman Figure in Barbier’s Poetry:

The section of Auguste Barbier’s (1805-1882) poem titled “La Curée,” published in Revue de Paris on September 19, 1830, related to “freedom” is as follows:

“…It is true that freedom is not a countess

from the noble Fauborg Saint-Germain,

a woman who faints at the slightest cry,

powdered and rouged.

She is a strong woman, with her chest thrust forward,

with her harsh voice and cruel charm,

with her tanned skin and sparkling eyes,

she walks with alert, large strides.

She takes pleasure in the clamor of the people in bloody street fights,

in the excited drumming sounds,

in the smell of gunpowder, in the distant succession of

church bells and cannons.

She only loves those from the midst of the people,

she only presents her broad bosom to the people,

to those who are as strong as her and want to embrace her,

with arms stained with blood…”[5]

Delacroix’s interest in literature is a well-known fact. Baudelaire refers to him as a “painter-poet.”

This woman figure in Barbier’s poem is also in an unconventional style not typically seen in that era. It is said that Barbier and Delacroix were close, and it is mentioned in the interpretations of this artwork that Barbier’s poem had an influence on it.

4-Anne Charlotte D.:

It is said that another inspiration for this female figure comes from a woman named Anne Charlotte. This woman is said to represent all the women who actively participated in the revolution and is also the main character of an event said to have taken place during the same period. This young girl, who worked as a laundress, goes out to search for her brother who is fighting in the streets on July 27 and finds him dead. Afterwards, she shoots herself with 10 bullets, 9 of which are aimed at the Swiss guards, while the last one takes her own life. Anne Charlotte is a revolutionary.

However, Anne Charlotte is not alone; she is just one example and a symbol. Women actually participated in this revolution. There are no deceased women on the commission’s list, but there are 52 injured women. One of them fought with a royal guard using a kitchen knife. The other women uprooted and threw paving stones and took care of the wounded.[6]

b-Bourgeoisie Figure:

The figure depicted on the left side of the painting, holding a rifle, is said to represent the bourgeoisie class that participated in the revolution, as indicated by the top hat on their head.

Visual (10): Detail

There are two different theories regarding this figure. One theory suggests that it could be Etienne Arago, one of the founders of Le Figaro newspaper. This theory has been widely accepted to the point of certainty. However, another theory proposes that the figure represents Delacroix himself. This theory was put forth by the renowned writer Alexandre Dumas, and Delacroix did not oppose it. The reason behind this remains unknown as to whether it is true.

Dumas’ interpretation states that Delacroix is a warrior. Although he comes from the upper class and did not directly participate in the revolution, he fought his battle on canvas with his brush. This canvas and brush are associated with the weapon depicted in the figure.

c-Street Urchin Figure:

The child depicted in the painting, holding pistols in both hands and standing beside the Figure of Freedom, is said to symbolize street children. In fact, in 1832, a police chief wrote that it was homeless street children who carried the first stones to the barricades and stood at the forefront of the resistance. The black cap on the child’s head is also a symbol of rebellion.

Visual (11): Detail

This street urchin figure would later inspire Gavroche in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, which was written 30 years later. Victor Hugo was influenced by this figure in the painting. The artwork Freedom Guiding the People was both influenced by literature and influenced literature in this way.

One of the bodies in front is missing pants. However, what is different here is that the figure is not actually without pants. It is portrayed with a single sock to convey the impression that someone has pulled down the pants, leaving only one sock. This figure makes a reference to a group called “sans culottes,” which was a revolutionary group. While the bourgeoisie class wore knee-length pants, the working class wore long pants. It represents the working class.

Visual (12): Detail

d- Other Figures:

Another young figure in the painting is depicted on the left side, with wide-open eyes, holding a sword in one hand and grasping paving stones with the other. This figure is wearing a hat similar to the ones worn by infantry soldiers. It is known that students actively participated in the revolution.

Visual (13): Detail

The figure of a wounded man kneeling in front of the Figure of Freedom is identified as a worker who temporarily came to Paris for work, as evident from his attire. The colors of his clothing also match the colors of the French flag.

Visual (14): Detail

The flag depicted in the painting is a commemoration of the 1789 Revolution. This flag, officially adopted on February 15, 1794, was proposed by the painter Jacques Louis David to have the navy blue color near the pole. Red and navy blue are the colors of Paris. After the Republic, the flag returned to the white flag, but after the 1830 Revolution, the tricolor flag was once again used. By using this flag and its colors in the painting, Delacroix conveys a revolutionary and republican message.

One of the bodies on the ground is an Swiss Guard, distinguished by his gray-blue uniform adorned with red trim and a plumed hat.

Visual (15): Detail

The adorned corpse represents the Swiss Guards, who were prominent figures opposing the revolution since their establishment in 1453. During the July Revolution, these figures were withdrawn. Delacroix emphasized through this painting that military power would not stand in front of the people.

The new king purchased this artwork, but due to the possibility of inciting the public, it could not be displayed. In fact, King Louis Philippe loved the painting very much, but this unease prevented its exhibition. It was eventually displayed when Louis Napoleon became president. However, it was not exhibited until 1863. In 1862, it was housed in the Luxembourg Museum, and in 1874, it was transferred to the Louvre. In the early 1990s, this painting was depicted on 100 franc banknotes in France.

Delacroix created this painting in the autumn of 1830 and it was exhibited in May 1831. As mentioned before, the painting intertwines allegory and reality. Each figure can convey multiple meanings and evoke various associations in different contexts. For example, the Figure of Freedom. Additionally, the other figures symbolize different segments of society, indicating that the painting as a whole carries symbolic significance. Over time, the painting itself became a symbol and an emblem of revolution. A similar artwork depicting the Republic was created by Zeki Faik İzer in Turkey in 1933.

The Statue of Liberty in New York was inspired by the woman in Delacroix’s painting, and it was a gift from France to the United States. However, American authorities found the semi-nudity inappropriate and modified the statue by covering the exposed breast of the woman.

References:

Arıkan, Hakan. (2016). “Reinterpretation of Eugene Delacroix’s Painting ‘Liberty Leading the People’ in the Context of Intertextual References.” Eskişehir Osmangazi University Journal of Social Sciences, 17(2), pp. 49-60.

Prideaux, Tom. (1966). The World of Delacroix 1798-1863. Time, Inc.; F edition, 1966.

Pınarbaşı, S. (2016). “Liberty Leading the People: Allegory, Literature, and Reality.” Art-Sanat Journal / Issue 9, pp. 121-142.

http://azizyardimli.com/fransiz_devriminden_napoleona/00_fransiz_devrimi2.html

https://www.wikiart.org/en/eugene-delacroix/all-works

http://www.leblebitozu.com/romantizm-akimi-ressamlari-ve-eserleri/

[1] http://www.ressamlar.gen.tr/eugene-delacroix-kimdir-hayati-biyografisi/

[2] http://www.leblebitozu.com/romantizm-akimi-ressamlari-ve-eserleri/

[3] Simge, Özer Pınarbaşı, «HALKA ÖNDERLİK EDEN ÖZGÜRLÜK: ALEGORİ, EDEBİYAT VE GERÇEKLİK», Art-Sanat Dergisi / 9 (Aralık 2018), s.123

[4] a.g.m., s.123-124

[5] A.g.m. s.128

[6] A.g.m. s.129

[7] A.g.e. s.139

Image 1: Eugene Delacroix’s artworks – WikiArt. Retrieved from: https://www.wikiart.org/en/eugene-delacroix

Image 2: “Massacre of Chios” by Eugene Delacroix – WikiArt. Retrieved from: https://www.wikiart.org/en/eugene-delacroix/massacre-of-chios

Image 3: “Scenes from the Massacre of Chios” by Eugene Delacroix – WikiArt. Retrieved from: https://www.wikiart.org/en/eugene-delacroix/scenes-from-the-massacre-of-chios-1822

Image 4: “The Women of Algiers in Their Apartment” by Eugene Delacroix – WikiArt. Retrieved from: https://www.wikiart.org/en/eugene-delacroix/the-women-of-algiers-in-their-apartment-1834-1

Image 5: “Death of Sardanapalus” by Eugene Delacroix – WikiArt. Retrieved from: https://www.wikiart.org/en/eugene-delacroix/death-of-sardanapalus-1827-1

Image 7: “Libertas” – Civil Wars of Rome. Retrieved from: http://www.humanities.mq.edu.au/acans/caesar/CivilWars_Libertas.htm

Image 8: First Seal of the French Republic – University of Oregon. Retrieved from: http://pages.uoregon.edu/dluebke/301ModernEurope/FirstSeal.jpg

Image 9: “July 28: Liberty Leading the People” – Analysis – Artble. Retrieved from: https://www.artble.com/artists/eugene_delacroix/paintings/july_28:_liberty_leading_the_people/more_information/analysis

Image 10: “Detail from Liberty Leading the People” – Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0f/Eug%C3%A8ne_Delacroix__Liberty_Leading_the_People_%28detail%29_-_WGA6179.jpg

Image 11: Eugene Delacroix – Artble. Retrieved from: https://www.artble.com/imgs/b/d/4/134968/530556.jpg

Image 12: Eugene Delacroix – Artble. Retrieved from: https://www.artble.com/imgs/b/d/4/134968/939811.jpg

Image 13: Eugene Delacroix – Artble. Retrieved from: https://www.artble.com/imgs/b/d/4/134968/213342.jpg

Image 14: Eugene Delacroix – Artble. Retrieved from: https://www.artble.com/imgs/b/d/4/134968/703042.jpg

Image 15: Eugene Delacroix – Artble. Retrieved from: https://www.artble.com/imgs/b/d/4/134968/862158.jpg