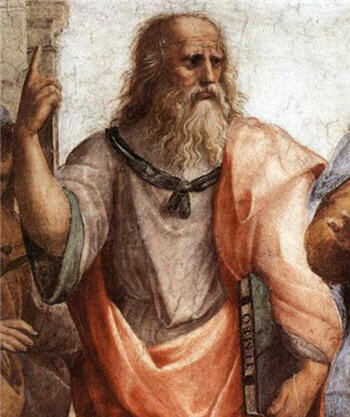

King of the Collectors: Charles I

After Charles I was tried and executed in 1649, his fabulous art collection was sold off piecemeal on the orders of Oliver Cromwell. William Cook previews an exhibition at the Royal Academy that brings the treasures amassed by Charles together again for the first time in 370 years.

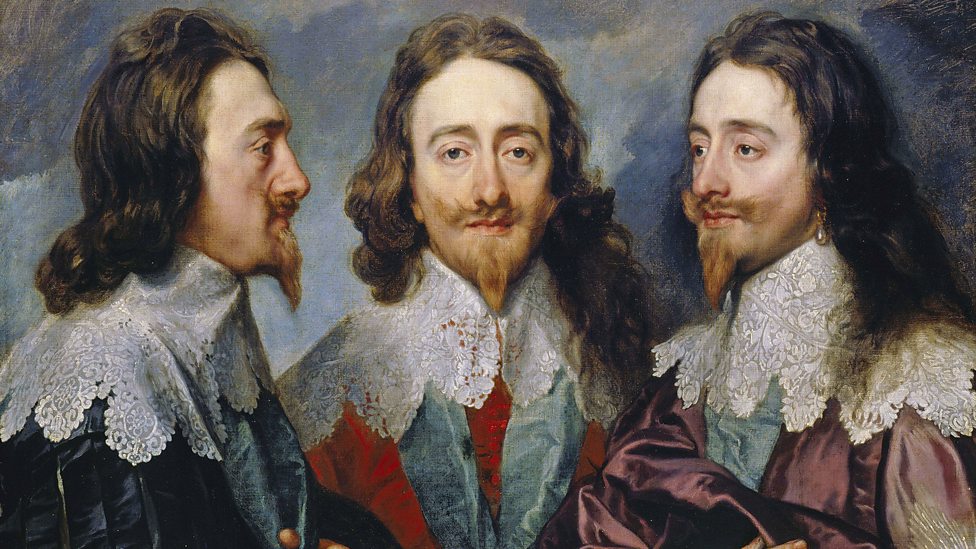

- Anthony van Dyck, Charles I

At 2pm on Tuesday 30th January 1649, King Charles I stepped out of London’s Banqueting House, and onto the scaffold. ‘I shall go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown,’ he said, as he put his head on the block. The executioner swung his axe, and England became a Commonwealth. Charles’s ardent belief in the supremacy of the monarchy over parliament ignited the English Civil War, resulting in 300,000 deaths – 6% of the population. As a monarch, he was a disaster – but he had great taste in art. He left behind the finest art collection ever assembled by a British monarch, and now London’s Royal Academy has reunited the greatest hits of his collection. ‘This is a once-in-a-lifetime occasion when we can show them together,’ says Per Rumberg, co-curator of this extraordinary exhibition. Charles’s interest in art began in 1623, when he went to Madrid to court Maria Anna, daughter of King Philip III of Spain. The engagement was broken off after fierce opposition from English Protestants, who feared this betrothal would give Europe’s strongest Catholic dynasty control of the English Crown.

Yet while he was in Spain, Charles saw the glories of its royal art collection. ‘He was mightily impressed,’ says Rumberg. Charles came home without a bride, but with paintings by Titian and Veronese, and a burning ambition to acquire a great art collection of his own. When Charles became King, in 1625, he set about assembling a collection to rival the one he’d seen in Spain. None of his predecessors had collected much – he had a lot of catching up to do. Over twenty years, he amassed 2000 artworks. ‘He spent a huge amount of money – it was hugely political’ says Rumberg. ‘It had to be funded, and signed off by parliament, and parliament wasn’t too keen because they needed money for wars.’

- Aphrodite (Crouching Venus)

- Titian, The Supper at Emmaus, c.1530, Louvre Museum – Paris

Charles was especially keen on the Italian artists of the Renaissance (one room in his palace at Whitehall was hung floor to ceiling with Titians) but his biggest coup was persuading two of Europe’s finest contemporary painters, Rubens and Van Dyck, to come to Britain. Van Dyck became his court painter, giving us an intimate record of the character of Charles I. Charles was an Anglican, not a Catholic, but his collection betrays his sensibilities. Its focus is Catholic Flanders, rather than the Protestant Netherlands.

Charles’s interest in fine art wasn’t merely aesthetic. These baroque pictures were status symbols – an expression of his authority, and his affinity with France and Spain. Like the Kings of France and Spain, Charles was a devout believer in the Divine Right of Kings – the idea that the monarch is God’s own servant, answerable to God alone.

In France and Spain, art was employed to bolster the godlike authority of these absolutist monarchs. Likewise, Rubens’ opulent paintings reinforced Charles’s vainglorious image as an enlightened autocrat. Charles liked these pictures, but he didn’t just collect them because he liked them. They were an affirmation of his right to rule. After he’d signed Charles’s Death Warrant, Oliver Cromwell sold off this collection, at Somerset House. This sale was open to the public – anyone could come along. The main aim was to raise money (after five years of Civil War, the government was terribly short of cash) but it was also symbolic.

- Anthony van Dyck, Queen Henrietta Maria with Sir Jeffrey Hudson, 1633, National Gallery of Art, Washington

‘It was a political statement,’ says Rumberg. ‘It wasn’t only enough to chop his head off – the pictures had to go as well.’ Many of the best pictures went abroad. Most ended up at the Prado, in Madrid, or in Paris, at the Louvre. In Britain, Renaissance art was still a new-fangled notion. Charles’s Titians returned to the Continent, where they were better known – and understood.

- Andrea Mantegna, Triumph of Caesar: The Vase Bearers, c. 1484-92

Cromwell’s civil servants kept a detailed record of this sale, which provides an intriguing overview of the art market in the 17th Century. A Raphael sold for £2000 (a colossal sum at a time when a skilled labourer would be glad to earn a shilling a day) while a Rembrandt sold for only £6. These bills of sale have been invaluable in tracing Charles’s artworks. The RA have reassembled 150 of the most important works for this groundbreaking show. After Cromwell’s death, Charles II returned to England to reclaim the crown, and during his reign he strived to reassemble his father’s art collection. Most of the works which had been sold to British buyers were hastily returned, and remain in the Royal Collection to this day.

However many of the best works remained abroad, and it’s the return of these lost masterpieces which makes this exhibition so special. Four Titians are returning to Britain for the first time since the 17th Century, alongside Van Dyck’s most famous portrait of Charles I, now owned by the Louvre. Seeing these paintings together again gives you a fascinating insight into the tastes of Britain’s most maligned monarch, who started a Civil War and lost his head, but was Britain’s greatest patron of the visual arts.

- Anthony van Dyck, Charles I (‘Le Roi à la chasse’),1635, Louvre Museum, Paris

But to see the best and biggest painting in Charles I’s art collection, you need to visit the last remnant of his palace at Whitehall. Almost all of that splendid palace was destroyed by fire in 1698. Only the Banqueting House survives. The ceiling is adorned with an enormous painting by Rubens, commissioned by Charles I. When Charles walked out of this room, and onto the scaffold, it was the last thing he saw before he died.

Source : bbc.com